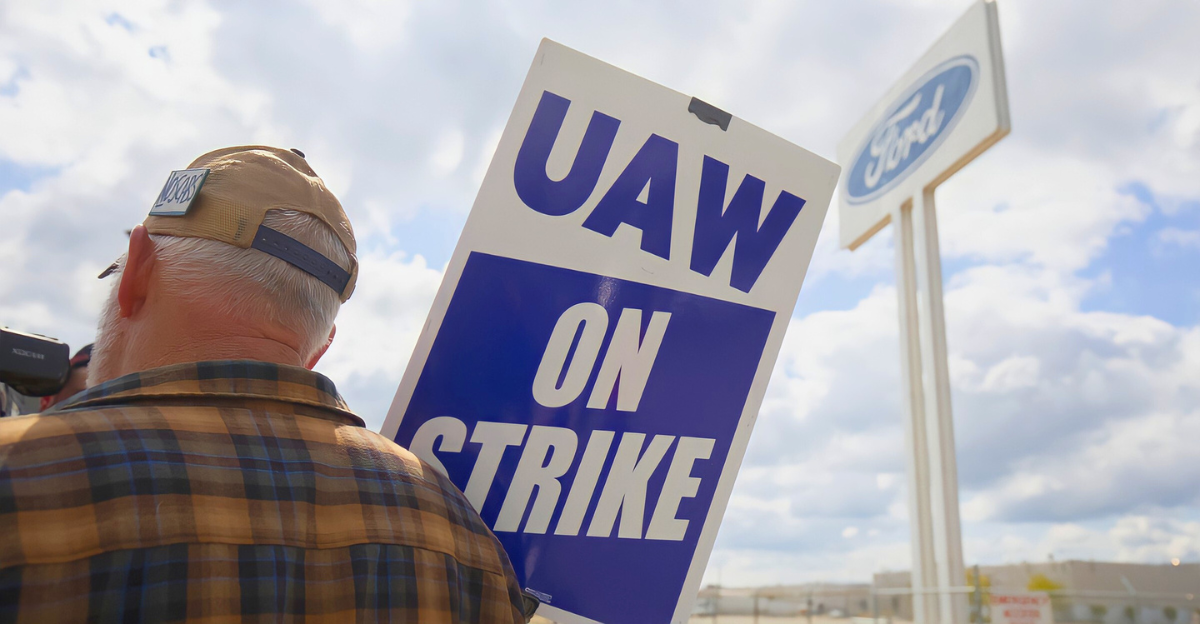

American auto manufacturing saw a dramatic upheaval on September 15, 2023, when about 12,700 UAW members walked off the job at three key factories – Ford’s Wayne Assembly (Michigan), GM’s Wentzville plant (Missouri), and Stellantis’ Toledo complex (Ohio).

For the first time in UAW history, all three Detroit automakers were struck simultaneously. Reformist UAW President Shawn Fain had secretly orchestrated this surprise “Stand Up” strike, catching executives off-guard.

Although the walkout involved only about 9% of the union’s ~145,000 members, it carried the clear message that more plants could be targeted if talks did not improve.

$250 Billion Backdrop

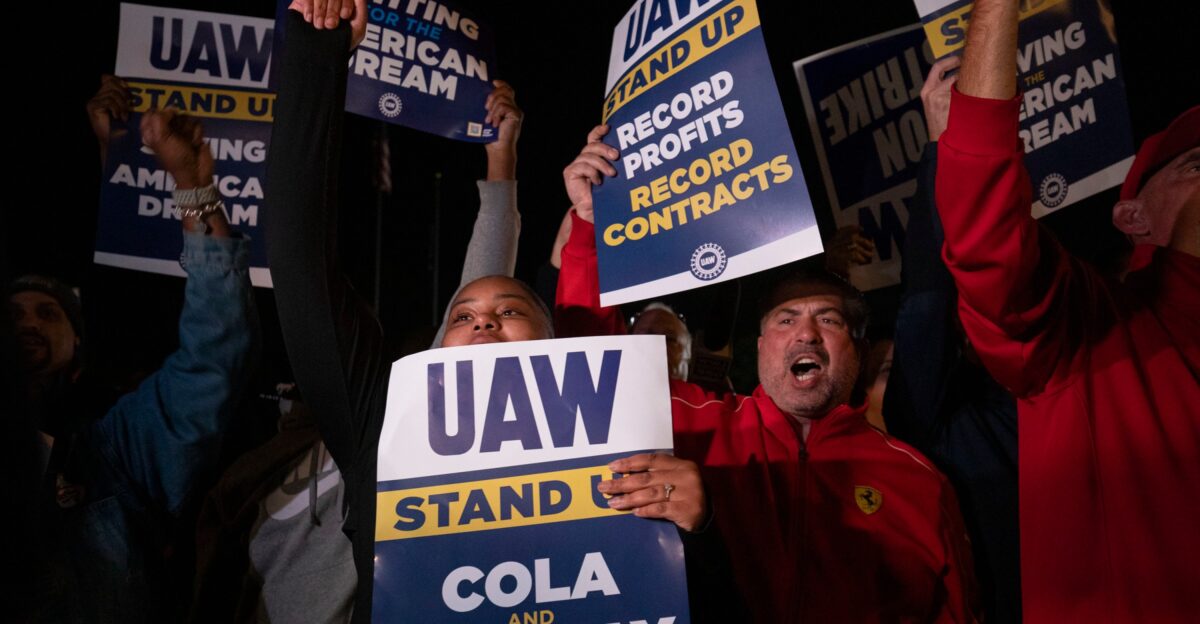

Meanwhile, the strike was unfolding against a backdrop of record profits and growing inequality. Over the past decade the Big Three had earned roughly $250 billion in profits, including about $21 billion in just the first half of 2023.

In contrast, the average autoworker’s real pay had fallen by roughly 19% since 2008. Corporate bosses prospered: Ford’s CEO made about $21 million and GM’s around $29 million in 2022 – hundreds of times more than rank-and-file earnings.

This widening gap between soaring executive pay and lagging worker wages gave autoworkers strong justification for demanding historic contract gains.

Decade of Concessions

For over a decade after 2008, UAW members had accepted deep concessions while companies rebuilt. The union agreed to two-tier wages (new hires earning far less than veterans), frozen cost-of-living raises, and other cutbacks.

By the last pre-strike contract in 2019, workers received only about 6% total raises over four years, even as inflation ran roughly 18%.

Many members felt these lasting cuts betrayed their sacrifices. Under Fain’s leadership – the first president elected directly by rank-and-file – the union vowed to use the strike to reverse years of unpaid concessions and reclaim lost ground.

Mounting Pressure

As negotiations unfolded in summer 2023, Fain publicly railed against “corporate greed” and warned that Ford, GM and Stellantis would all face a strike unless talks improved.

The UAW’s opening demands were sweeping: roughly a 40% wage hike over four years, full inflation adjustments, equal pay for all (ending two-tier rates), richer pensions and retiree benefits, and even the right to strike over plant closures.

The Big Three’s initial offers – roughly 10–15% raises plus one-time bonuses – fell far short. By the Sept. 14 contract deadline, no agreement was in sight, and union officials braced for a walkout as midnight approached.

“Stand Up” Strategy

That night at 12:00 a.m. on Sept. 15, the UAW launched its revolutionary “Stand Up Strike.” Instead of hitting every plant at once, the union quietly struck one major assembly plant per company: Ford’s Wayne facility, GM’s Wentzville truck plant, and Stellantis’ Toledo Jeep plant.

Stellantis spokesperson Jodi Tinson later said management learned of the walkout around 10 p.m. – “like everyone else,” she quipped.

By initially halting only the most profitable lines, the union maximized pressure while keeping other factories in limbo.

Fain explained that this tactic gave negotiators “maximum leverage and maximum flexibility” as companies scrambled to guess where and when the next strike would come.

Production Paralysis

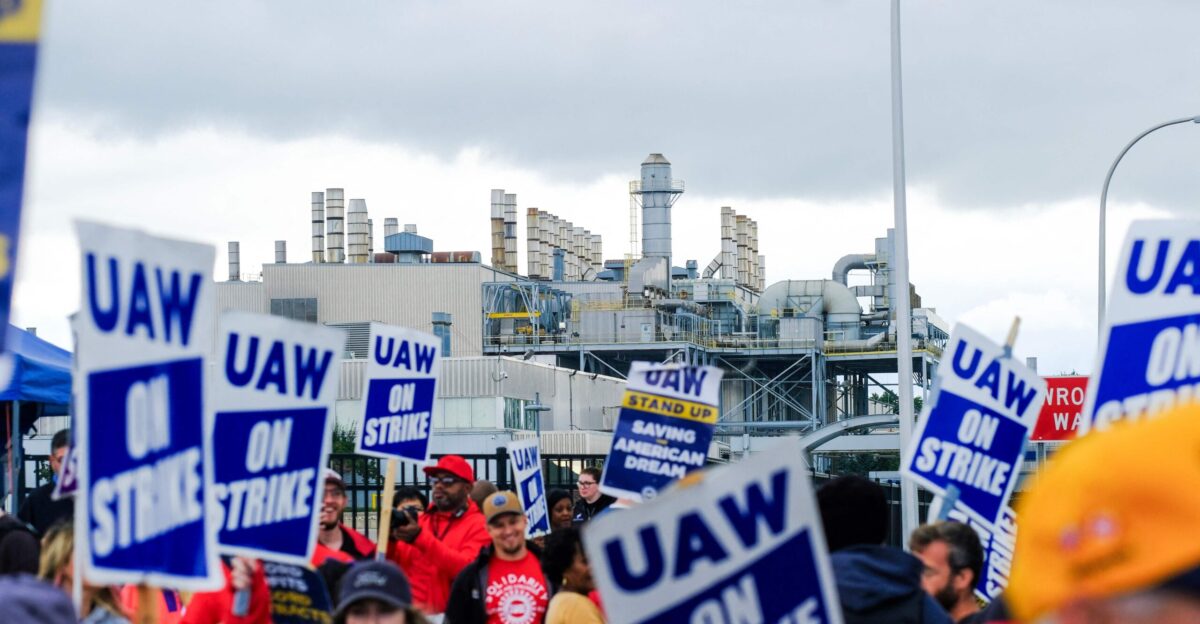

The targeted strike hit the supply chain like a shockwave. Ford’s sprawling Wayne plant (making Broncos and Rangers) went silent, as did GM’s Wentzville plant (Chevrolet Colorados) and Stellantis’ Toledo plant (Jeep Wranglers).

Analysts estimated these stoppages trimmed production by roughly $400–$500 million per week at the peak.

Suppliers felt the pinch immediately: Eagle Industries prepared to furlough 75% of its workforce, and CIE Newcor announced plans to cut 300 jobs across Michigan facilities.

By late September, more than 25,000 UAW members were on strike across 38 sites, and thousands more auto-parts workers were laid off until the walkouts ended.

Workers’ Stories

For many UAW members, the strike was deeply personal. Ford assembler Britney Johnson, picketing in Wayne, carried her family’s legacy: four generations before her built a middle-class life from these factory jobs.

Her mother, retiree Tracy Brooks, smiled and joked, “We told Britney Johnson … she’s representing our family”.

Brooks added, “It meant a lot, being in the union,” recalling how those “good jobs” let Black families like hers buy homes, cars and send their children to college. For her family and others in Detroit, union wages had long been a path to opportunity.

Presidential Precedent

At the height of the conflict, President Joe Biden made history on Sept. 26 by joining striking workers on the picket line at GM’s Willow Run facility.

Wearing a UAW cap, he told them through a bullhorn: “You deserve the significant raise you need”, and noted that the automakers “have done incredibly well, and now it’s time for them to step up for us”.

The White House arranged this rare show of support with little notice, surprising many CEOs.

The visit gave striking autoworkers powerful political backing, even as opposing candidates rushed to court them in hotly contested Midwestern states.

Economic Shockwaves

The strike’s economic shockwaves were enormous. Analysts estimated it cost about $3.95 billion in lost output in just the first two weeks. By late October, nearly 46,000 UAW members were on strike across 38 factories in 20 states.

Even the Federal Reserve took notice, reporting that the walkout “subtracted about 0.1 percentage point from GDP growth” in Q3 2023 and 0.5 in Q4 – in effect “tapping the brakes” on auto production.

Anderson Economic Group’s chief economist warned that once “innocent bystanders begin to feel it,” public support for the strike could wane.

In all, observers agreed that a relatively small strike had shown how organized labor could slow national economic activity.

Victory’s Implications

Ultimately, the UAW achieved a historic win. By late October, contracts were ratified granting roughly 25% base pay raises over 4½ years (about 33% with inflation pay bumps).

The destructive two-tier pay system was eliminated, and cost-of-living wage increases were restored. Crucially, workers also won the right to strike over plant closures – a major new leverage tool.

The outcome was so substantial that non-union competitors even raised pay: Toyota, Honda and others quickly announced higher wages for their U.S. factories.

UAW President Fain declared the union had “begun to turn the tide in the war on the American working class”, and vowed next time to take on not just the Big Three but “the Big Five or Big Six” automakers.

Beyond the Big Three

The strike’s influence extended beyond Detroit. Within days, Toyota – long non-union – confirmed it was increasing pay for all its U.S. factory workers.

A Toyota executive explained, “We value our employees… and we show it by offering robust compensation packages”.

Industry observers noted similar moves at Honda and Hyundai.

In other sectors, major employers felt pressure too: airlines and tech firms pledged higher wages in the wake of the auto wins. In short, UAW members had raised the floor for factory workers everywhere, turning their negotiating victory into a broader labor leverage across industries.

Broader Labor Momentum

News of the UAW’s success energized other unions. In March 2024 the UAW-backed unionization drive at Volkswagen’s Chattanooga plant succeeded for the first time in that facility’s history.

Boeing machinists, UPS drivers and teachers were among those who cited the auto strike as inspiration.

UAW leaders made that explicit: as Fain put it, “non-union auto workers are not the enemy…they are our future union family”.

He vowed that when the UAW returns to bargaining in 2028, it will be pushing not just the Big Three but all the Big Five (and even Big Six) automakers, signaling a drive to organize beyond its traditional base.

Ongoing Uncertainties

However, not every issue vanished. Some union members warned that companies might not keep all promises. For example, Stellantis has faced accusations of not fully fulfilling its pledge to reopen the formerly idled Belvidere, Illinois, plant, spurring local leaders to demand enforcement of the deal.

Meanwhile, economists and executives scrambled to absorb the higher labor costs.

The automakers remained profitable, but the industry must now invest in automation and electrification without alienating workers.

Observers note that the strike has reshaped future contract talks: companies expect more pressure, and communities are watching whether the benefits stick.

The Next Chapter

Looking forward, union and corporate leaders alike view the 2023 strike as a turning point. The UAW has already poured new resources into organizing drives – reportedly investing tens of millions to unionize EV battery plants and other non-union sites.

At the same time, the deal’s gains set a new precedent across the auto industry and beyond.

Yet challenges loom: automakers warn that shrinking demand or heavier regulation could force tough trade-offs.

As one labor strategist noted, the Stand Up strike has taught both sides “how much power the other has.” In essence, Detroit’s 2023 showdown has rewritten the script for U.S. labor disputes.

Conclusion

The UAW’s 2023 “Stand Up” strike will be studied as a rare demonstration of union strength. In this long arc – from surprise midnight walkouts to a landmark contract – autoworkers reclaimed decades of deferred pay and ended structural inequities.

Their victory forced employers, policymakers and even competitors to adjust.

For now, UAW members have a renewed sense of agency: they won far more than they dreamed possible.

Whether this becomes the start of a broad labor renaissance or a unique milestone in a long decline remains to be seen.